UCLA course teaches students to be better health care professionals for disabled people

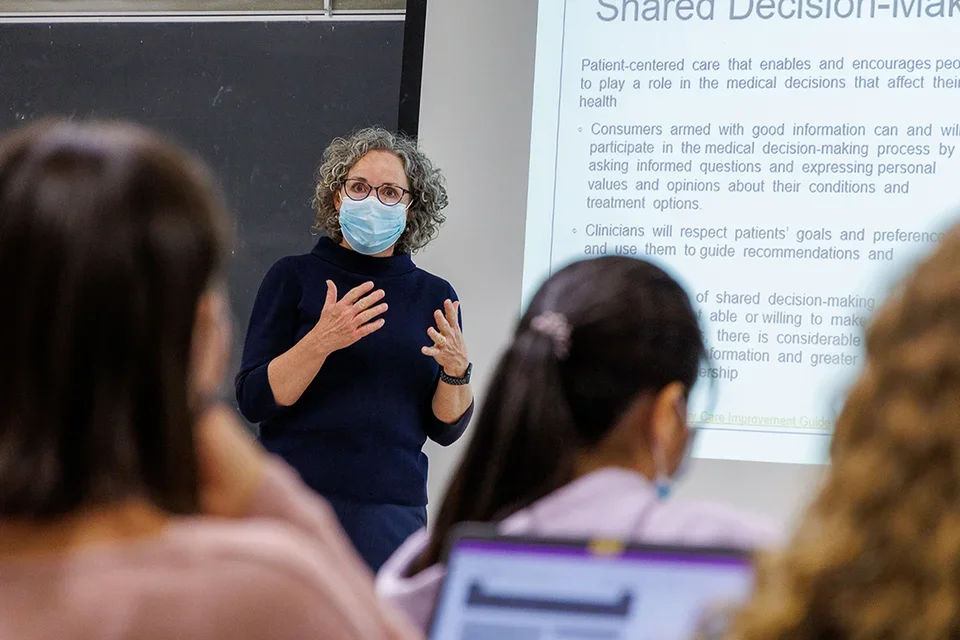

The students in nursing professor Lauren Clark’s class sat rapt as guest speaker Susy Thiele described a recent frustrating visit to see a gynecologist.

Thiele, who lives with cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair, was told prior to her appointment that there would be a lift to assist her onto the exam table. But when she got there, they could not accommodate her in her wheelchair.

“It’s kind of wrong and sad that in our day and age, the technologies that they might have — you know, the simple things, there just in case — aren’t there,” Thiele said.

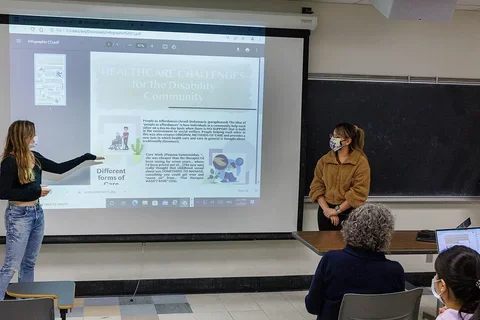

Thiele and her caregiver, Mary Esquivel, were speaking to the students in Clark’s “Care Work: Disability Justice & Healthcare,” a course designed for nursing and other health care-related majors that was offered for the first time at UCLA this winter quarter. During the 10 sessions, students explored different models of disability care and the disability justice movement.

“I think this is an important historical moment to influence a group of students,” Clark said in an interview outside of class, pointing to a new social justice movement around disability advocacy that is gaining momentum and picking up where the disability rights activists of previous decades left off. Moving away from formal channels of legal action and policy change, the contemporary movement is instead turning to community building to ensure access and support for those living with disabilities, she added. In action, this looks something like that second-to-last class.

“There's a famous saying in the disability community: ‘nothing about us without us,’” said Clark, who was thrilled that community members like Thiele joined the class that day.

Thiele, who is involved with Momentum (formerly the United Cerebral Palsy of Los Angeles and now a partner of UCLA), was joined by five other Momentum members — who attended via Zoom — eager to share their experiences and ideas for students to become health care professionals more clinically adept at working with disabled people.

A labor of love

For Clark, disability justice is more than just the focus of her class.

“My interest in disability and care comes from a personal place,” said Clark, who has an adult son with an intellectual disability. Navigating the health care system and its challenges “was hard work for our family and very hard work for our son.”

It makes sense that Clark came to campus in 2019 to become the inaugural Shapiro Family Professor in Developmental Disability Studies at the UCLA School of Nursing. Ralph and Shirley Shapiro and their children, Alison and Peter are all philanthropists who support UCLA and they founded the Shapiro Family Charitable Foundation in 1984. The family has been dedicated to developmental disability studies at UCLA, supporting research initiatives that have pushed the campus to become a leader within the University of California system. In 2007, UCLA became the second UC to offer a disability studies minor.

To channel her personal interest in improving how the health care system works with people who have disabilities into her work as a professor, Clark partnered with UCLA’s disability studies program, which awarded grants to faculty to help them develop new classes. The $5,000 grant enabled Clark to hire a teacher’s assistant and launch “Care Work,” an interdisciplinary and co-listed course between disability studies and the nursing school — the first of its kind at UCLA. Clark, who is also a public health nurse and anthropologist, said it was “too golden” of an opportunity to pass up.

Clark worked with Victoria Marks, chair of the disability studies minor, to help her structure the class and develop its learning activities and content. Pia Palomo, the disability studies program’s academic coordinator, and Caitlin Solone, the disability studies academic administrator, were also instrumental in planning the course.

“As part of the larger project of challenging and changing society’s attitudes towards disability, ‘Care Work’ will build important bridges between the experience of human difference and change, disability as a social issue and the ways in which the medical establishment treats and understands disability,” said Marks, who is also a professor in the department of world arts and cultures/dance in the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture.

In January, internationally renowned disability rights activist Judy Heumann spent a week at UCLA as a Regents Lecturer. Heumann, who served in the Clinton and Obama administrations, spoke to Clark’s class, where she engaged students in an interdisciplinary discussion on disability policy.

For second-year student Katie Mayo, the experience left her starstruck.

“That was such an awakening and a humbling experience,” said Mayo, who is a psychology major and a disability studies minor. Mayo was among 23 students who took Clark’s class.

Learning outside the classroom

The other major component of the class was its companion course, a three-unit community engagement opportunity during which students would go into a disability service setting through Momentum (such as an independent living center) to see firsthand what care work looked like and where it fell short.

Savannah Lopez, a second-year neuroscience major and disability studies minor, and eight other students in the course worked with the organization at multiple locations throughout the area. Momentum assigned a person with a disability to each student so that they could spend time together during the quarter.

As winter quarter came to an end, Lopez said she has no intention of ending her frequent visits with her mentor, Sherry Golden.

“I’m making this about building a connection,” said Lopez of Golden, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair. “We were able to build such a great relationship.”

Golden shared her perspectives with Lopez, like the importance of language in building inclusivity, such as using “serve” instead of “help.”

Lopez said that these simple language choices change the relationship between individual and care worker.

Lopez and Golden also had more complex conversations, exploring the intersections between disability, race, gender and sexual orientation, and discussing genetic screening and testing of fetuses as means of terminating pregnancies in which disabilities are detected.

“I feel like without this class I really would just keep walking about my day, not noticing all the inaccessibility around me,” Lopez said.

Clark said she initially thought that interactions between students and their counterparts in the disabled community might be limited to playing cards or going on walks. Once students started sharing what they were covering in the class with their community partners though, many of the partners wanted to be involved in the conversation, which Clark was enthusiastic to facilitate.

In the second-to-last class of winter quarter, Thiele and the others from Momentum joined in a discussion on preparing a disability-competent health care workforce.

“Sometimes nurses and doctors are under the impression or make the assumption that you don’t speak,” said Thiele to the class, explaining that just because someone has a communication impairment such as dysarthria (a motor speech disorder where the muscles of the mouth are compromised) it doesn’t automatically mean that person has a “thinking impairment” or intellectual disability.

Thiele, who is a published author, quickly turned this notion on its head, as did another Momentum speaker that day, Brandon Mendenhall, founder of the heavy metal band the Mendenhall Experiment and subject of the 2019 Netflix documentary “Mind Over Matter.”

Mendenhall, who was born with cerebral palsy, talked with students by sharing how learning to play guitar without the use of his left hand got him out of his bubble.

Mendenhall joined a handful of students and others from Momentum who stayed on Zoom after the class to keep talking. He also made a plug for his upcoming show, inviting his new connections to join him as VIP guests at a rehearsal before the performance.

“It is really about the synergy between academic programs and community learning, and how UCLA isn't just the ivory tower on the hill but a portal for students and for the community to come together to learn important things about disability justice,” said Clark, who sees her teaching position as an opportunity to grow the line of inquiry around disability and nursing together.

“I think that's the promise of higher education that we forget about.”