Homeless Health Care

When you live on the streets, life is grueling. And stressful. Your focus is survival. Where do I sleep? Where do I eat? Health care—and healthy living—are low priorities when the most basic of human needs are in question.

But when the days turn into weeks, and, then, months (and, perhaps, years), the toll can be staggering.

Bodies take a beating when you live on the street. In addition to exposure to the elements and the risk of assault, chronic issues go untreated and can spiral out of control.

When you are homeless you spend a lot of time standing—sometimes barefoot or in poorly fitting shoes. The food you eat tends to have a lot of carbohydrates, which makes it difficult to control diabetes and weight. Infectious diseases can spread rapidly in homeless populations due to the close proximity and lack of proper hygiene.

You don’t have a regular doctor, so if you do get sick or injured, you head for the emergency room—or just let it go.

For homeless children the consequences are dire. Research from the Children’s Health Watch (published in 2016) has shown that children who experienced homelessness had higher rates of hospitalization, and that risk was compounded for children who were homeless both prenatally and post-natally.

All of which begs the question: who is leading the charge to improve health care for the homeless?

Nurses.

In fact, nurses and nurse practitioners account for nearly 40 percent of the health care for the homeless clinicians’ network membership while physicians account for 17 percent. Nurses act as social workers, therapists, and advocates; they work in clinics, shelters, and on the streets.

Nurses are getting things done.

Providing hope for better health

Thirty-five years ago, the Union Rescue Mission in downtown L.A. contacted the UCLA School of Nursing with an intriguing request: Would the school be interested in providing healthcare services for the residents of the mission?

Back then, little was known about L.A.’s homeless population, much of which coalesced around the gritty skid row area of downtown. This area, a mere 15 miles east of the UCLA campus, may as well have been a continent away. Few health care providers knew how to reach or even treat this forgotten sliver of humanity that remained out of sight and out of mind for most Angelenos.

“At that time, there was little data on the homeless,” recalled Ada Lindsey, who was dean of the School of Nursing when the request was made. “Nobody really knew whether they would come to any clinics for health care or whether they would come back for follow-up visits. Nobody even knew much about what kinds of health problems they had.”

But the prospect of reaching out to this underserved transient population and learning from these experiences generated excitement at the school. The answer to that intriguing question was “Yes.”

Today, the UCLA School of Nursing Health Clinic at the Union Rescue Mission is a national model for its delivery of health care to the poor and the homeless. It is one of the oldest and largest clinics of its kind in the country. And it is the only shelter-based health clinic in the city that provides health care, not just for homeless men, but women and children as well.

The clinic provides for basic needs including acute and primary care, medications on-site and prescriptions, and basic lab work. Since its founding, the facility has provided care in more than 250,000 patient visits. In 2016, the staff administered comprehensive medical services to more than 2,500 people. For the past several years, the clinic has been a sub-recipient of the North East Valley Health Corporation, a Federally-Qualified Health Center.

The clinic underwent a major reorganization last year and is now staffed by two nurse practitioners and two licensed vocational nurses. The physical environment of the clinic has also been transformed, thanks to donations of new exam tables and other equipment from Operation USA. Mattel Children’s Foundation donated toys and games to give children a chance to play while their family members receive care or attend workshops.

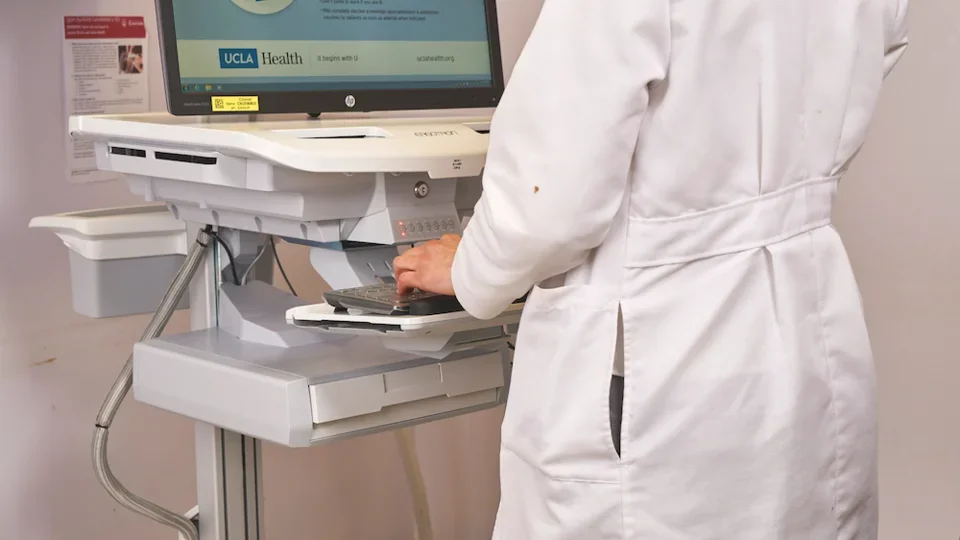

In addition, in January, the School installed an electronic health record system in the clinic thanks to two very generous donors, The Steven C. Gordon Family Foundation and Ralph and Shirley Shapiro Family Fund, and support from the UCLA Health System. The EHR provides improved continuity in care and the ability to interface with laboratory and diagnostic services.

Sabrina Friedman, EdD, DNP, FNP-C, PMHCNS-BC is the new clinical director of the Health Center and a provider of primary and psychiatric services.

“Patients seen at the clinic have medical issues similar to those in other environments, but much more severe,” said Dr. Friedman who began her career as a nurse practitioner 20 years ago working at what was the only federally-qualified health center service in the Southern Nevada area at that time.

“On an almost daily basis, we see hypertension that is dangerously elevated, uncontrolled diabetes, and exacerbations of COPD. Our patients may not have been treated for years, do not have the needed medications, or have not been diagnosed due to lack of regular check-ups.

“One of the biggest challenges we face,” Dr. Friedman shared, “is that our patients are not in a stable environment—they are on the move. Monitoring their chronic illnesses and providing follow-up is hard to do. Making and keeping regular appointments is tough, so we try and accommodate patients with same day appointments and on a drop-in basis.

“You realize that you have to care for them in the moment. You don’t say ‘where have you been? Why didn’t you come back?’ Instead, you say ‘let’s see where you are at and how we can get you back on track.’ Once the individual gets into a program, such as the one at the Union Rescue Mission, then health care can become a priority,” she added. “They can work on controlling their blood pressure or managing their diabetes.”

She estimates that a large percentage of the patients that are seen at the clinic suffer from mental illness. “Many suffer with bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia and sadly their mental illness may develop from living on street—depression, anxiety, PTSD from experiencing violence or seeing violence committed, and substance abuse.”

Dr. Friedman has been leading health education classes for the men in the URM Christian Life Development Program on topics such as diabetes, heart disease and Hepatitis C—with positive results. “Recently, I was able to inform the attendees about a study for a new Hepatitis C drug they might be eligible for that was going on across the street. Several of the men have enrolled and are very pleased to be receiving treatment.”

Dr. Friedman emphasizes that nurses care for the whole patient. The holistic approach serves this patient population well because of the complex situation that affects the patient—mentally, physiologically, socially. ‘We take our time with each patient because we want to make sure we’ve looked at the patient from all dimensions,” said Dr. Friedman. “We ask them questions such as, ‘Are you sleeping?’ ‘Where are you sleeping?’ ‘Are you afraid to sleep?’ ‘Have you eaten today?’”

For students at the School of Nursing, the clinic provides the opportunity to learn and experience working with this underserved population.

The Future is Unknown

There are many unknowns about the future of caring for the homeless here in Los Angeles, as well as across the country. On the positive side, in November, voters in the City of Los Angeles passed a measure to fund housing and shelters for the homeless and County voters recently passed Measure HHH which, through an increase in sales taxes, will provide more programs and services for this population. Any potential changes to the Affordable Care Act, which provides health insurance for the poor, may affect how care is delivered in the future, but it appears that Los Angeles is committed to helping its most disadvantaged.

The Frustrations and the Rewards

Caring for this population is not easy.

“There’s a fair amount of substance

abuse, and mental illness,” said

Dr. Friedman. “You can’t judge them.

It can be tiring and frustrating. But it can also be inspirational and rewarding, especially when it comes to caring for children.

“We are caring for people who are all but forgotten, but we are here for them and they are receiving good healthcare.”