Gardening: Growing Strong Mental Wellness

It began as a modest investment of space and money – an unused, raised outdoor planter bed at UCLA’s Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital and $350 worth of plants, soil and gardening tools.

But, with careful planning by a multidisciplinary team, the 2.5-foot by 10-foot plot yielded a popular therapeutic tool for some of the hospital’s inpatients and produced an important piece of research.

While there was a body of research into the therapeutic effects of gardening and other nature-related activities on people with mental illness in residential care facilities or in outpatient settings, no one had studied garden therapy for adults in an inpatient psychiatric hospital.

“It’s important to note that this is the first time gardening has been studied in an inpatient setting,” said Huibrie Pieters, an associate professor at the UCLA School of Nursing who headed the research project.

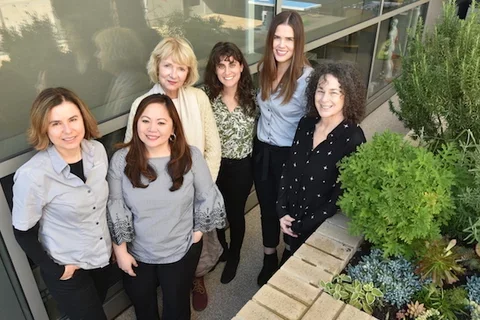

It all began in the fall of 2014, when Resnick patients told hospital staff members they longed for more programs outside. A multidisciplinary team of occupational therapists (Susie Clinton, Aimee Levine Dickman and Nancy Wicks), nurses and social workers at Resnick began working on the idea of creating a therapeutic garden, all the while eyeing that neglected raised bed on the hospital’s deck.

“It took a lot of planning, but I learned that even a small project can make a lot of difference,” said Leilanie Ayala, Magnet program director at Resnick, who approached Pieters in 2016 to collaborate on a research project. The work ultimately inspired Ayala to return to school and she is now a doctoral student at the School. Pieters said she had “been curious” about whether “green therapy” could benefit patients suffering from severe mental illness, but she went into the qualitative research project with “a very open mind, no expectations” that might color results.

Patients were involved from the start, even helping staff members choose plants – flowers, succulents and non- toxic herbs – that they helped place in the garden bed in the spring of 2015.

The research project ran from July 2017 to February 2018. Over that period, 25 in-patients were enrolled in the study. The participants represented a range of diagnoses, the most common of which were major depression and anxiety disorders.

Once a week, after a short preparation session, patients and staff went into the garden and worked together, planting, turning the soil, watering and harvesting flowers and herbs.

After their time in the garden, each patient was interviewed once by Ayala or a third study author, Ariel Schneider. Then a social worker at the hospital, she now works as a therapist in Santa Barbara offering therapeutic horticulture to Cottage Hospital inpatient and intensive outpatient program participants.

Results were overwhelmingly positive, with most patients reporting improvement in motivation, enjoyment of being in nature and social interaction.

“Well, the garden is kind of like a community of plants,” one patient noted, “I associate that with us going into the garden and being a community together and tending to it and taking care of it. And that kind of instills me to want to take care of myself in a way...I need to attend to my needs, too.”

Another patient said: “I did something productive. I felt good. It was a way of getting my mind off my problems.”

Still another observed: “I don’t feel so confined. Being at one with nature, it kinds of brings a sense of peace, and that’s why I’m more motivated to go outside and be interactive.”

Schneider said she had “a hunch that the patients were getting something from the group” as they conducted the interviews. “The quotes from the patients were so poignant...I was pleasantly surprised and excited to hear what they had to say.”

Pieters said she very impressed by the garden’s impact, especially for a relatively small financial investment.

“These are patien who are sick in a deep way,” she said, adding the extent of their social interaction around the garden was what stood out the most for her.

“These patients typically feel alienated and isolated. But being outside and gardening, the patients had a sense of being with others...and a very strong sense of belonging.’

With the garden therapy program still going strong, there are plans to expand it to other units in the hospital and to do additional research. Clinton and Wick continue to run the garden group each week for patients and are in the process of expanding the garden to include more planters.

Results of the research project, headed by Pieters and titled “Gardening on a Psychiatric Inpatient Unit: Cultivating Recovery,” was published last fall in the Archives of Psychiatric Nursing.

During the February 2019 announcement that Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital received Magnet status, the gardening project was identified as an exemplar of new knowledge, highlighting the support of nursing research, evidence-based practice and innovation.

“It’s truly a multidisciplinary study,” Pieters said. “Social work, nursing and occupational therapy, everyone working together. That’s kind of a big deal. We should be doing more multidisciplinary and holistic work.”